Can a Parkinson’s Drug Treat Macular Degeneration?

By Serena McNiff

HealthDay Reporter

WEDNESDAY, Sept. 16, 2020 (HealthDay News) — A drug long used to treat Parkinson’s disease may benefit patients with a severe form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a small clinical trial suggests.

One of the leading causes of vision loss in older people is a condition called dry macular degeneration. More than 15% of Americans over age 70 have AMD, and 10% to 15% of those cases go on to develop the more severe wet macular degeneration, which can cause swift and complete vision loss.

Typically, wet AMD is treated with injections of medication into the eye. Most people need several per year to keep the disease from progressing.

But this small, early-stage clinical trial suggests an alternative may be on the horizon: the leading drug used to treat Parkinson’s disease, called levodopa.

The trial was an outgrowth of a 2016 study that found Parkinson’s patients who took levodopa were less likely to develop macular degeneration.

“The study found a relationship between taking levodopa and macular regeneration,” said Dr. Robert Snyder, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Arizona, in Tucson. “It delayed the onset of both dry and wet macular degeneration, and reduced the odds of getting wet macular degeneration.”

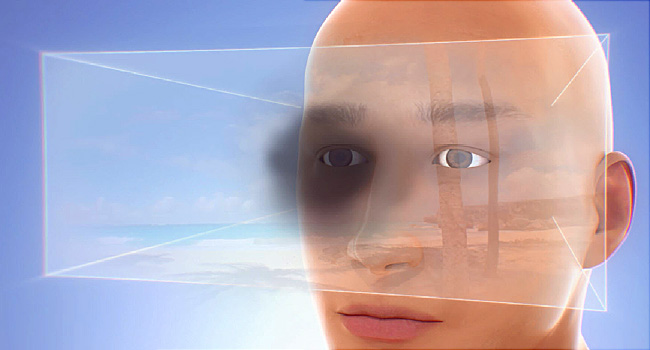

Macular degeneration affects the macula, part of the eye that allows you to see fine detail. Wet AMD happens when abnormal blood vessels grow under the macula; often, these blood vessels leak blood and fluid, causing rapid damage.

Snyder and two colleagues began a clinical trial in 2017 to learn whether levodopa might help prevent both forms of AMD.

Twenty patients newly diagnosed with AMD took part in the first trial. Each was given a small daily dose of levodopa for one month.

An eye doctor evaluated them weekly to determine whether they also needed an eye injection. Since the trial was based on preliminary research, the authors wanted patients to receive injections if necessary, to ensure that their condition wouldn’t worsen if the levodopa was ineffective.

“Instead of injecting them, which would have been the standard of care, we treated them with levodopa and followed them weekly to make sure they didn’t get worse,” Snyder said. “And if they did get worse, we sent them back for an injection.”

Continued

After one month, all participants joined 11 new enrollees in a second trial to evaluate levodopa’s safety and effectiveness at different doses.

While many participants needed an injection during the trial, they required fewer shots than would normally be given during a one-month period. Taking levodopa also seemed to delay the need for an injection, the study found.

The authors reported that taking levodopa improved participants’ vision overall. It also significantly decreased the buildup of fluid in the eye.

The drug was shown to be safe and well-tolerated, the researchers said. Patients who experienced side effects associated with the medication, such as nausea and blurred vision, were placed on a lower dose.

But this sort of “open-label trial” has some limitations. There was no point of comparison, such as a placebo; all participants received levodopa. And researchers and participants all knew what treatment was administered, potentially introducing bias to the results.

Dr. Raj Maturi, clinical spokesman for the American Academy of Ophthalmology, said confirming the drug’s safety and effectiveness will require a larger, more robust clinical trial.

Maturi also expressed concern about potential side effects of levodopa, especially given the age of the population that is affected by macular degeneration.

“You’re talking about a population of their 70s and 80s — they already have other things going on,” Maturi said. “An additional oral systemic drug that they will take for the rest of their life can significantly affect their quality of life. I’m always concerned about the side effect profiles of oral drugs that have to be taken for a long period of time.”

While the second part of the trial is ongoing, early results were published online recently in The American Journal of Medicine. Snyder said a larger study is forthcoming.

“We felt pretty strongly that we had a positive effect and had a proof of concept to go forward with a larger, placebo-controlled clinical trial,” he said. “That’s going to be our next step.”