Male fetuses’ sex hormones can affect female siblings before they’re even born : Shots

The Science of Siblings is a new series exploring the ways our siblings can influence us, from our money and our mental health all the way down to our very molecules. We’ll be sharing these stories over the next several weeks.

A sibling can change your life — even before you’re born.

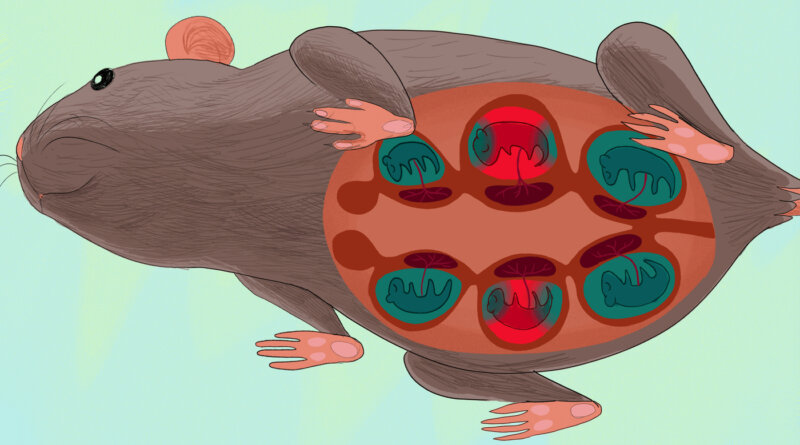

That’s because when males and females share a womb, sex hormones from one fetus can cause lasting changes in the others.

It’s called the intrauterine position phenomenon, or intrauterine position effects, and different versions of it have been observed in rodents, pigs, sheep — and, probably, humans.

“It’s really kind of strange to think something so random as who you develop next to in utero can absolutely change the trajectory of your development,” says Bryce Ryan, a professor of biology at the University of Redlands.

The phenomenon is more than a scientific oddity. It helped establish that even tiny amounts of hormone-like chemicals, like those found in some plastics, could affect a fetus.

An oddity in ancient Rome

Cattle breeders in ancient Rome may have been the first people to recognize the importance of a sibling’s sex.

They realized that when a cow gives birth to male-female twins, the female is usually sterile. These females, known as freemartins, also act more like males when they grow up.

Scientists began to understand why in the early 1900s. They found evidence that hormones from the male twin were affecting the female’s development.

The effect is less obvious in other mammals, Ryan says. Female offspring in rodents, for example, can still reproduce, but they have measurable differences in sexual development and tend to be more aggressive.

The intrauterine position phenomenon occurs because the testes of male fetuses begin producing testosterone early in development. Meanwhile, at this stage, the ovaries in females “don’t produce much of anything,” Ryan says.

This makes no difference when all the fetuses in a womb are of the same sex. But when males and females are present, there can be some hormonal cross-talk, especially in rodents, which can carry litters of a dozen or more pups.

“Those fetuses are packed so tightly together in the uterus, the testosterone can travel through the amniotic fluid from pup to pup and can also be carried by the circulatory system,” Ryan says.

Females squeezed between two males typically experience the most exposure to testosterone and are most likely to exhibit hormonal and behavioral differences throughout their lives.

BPA and other hormone-like chemicals

Usually, intrauterine position produces subtle changes that would matter only to a lab scientist or animal breeder.

But the phenomenon became part of a public debate in the early 2000s, thanks to a plastic additive called bisphenol A (BPA).

BPA acts like a weak version of the hormone estrogen, and studies showed that small amounts were leaching out of some plastics and into people.

At one time, scientists might have assumed these low exposures were harmless. But research on the intrauterine position phenomenon had shown that even trace amounts of a sex hormone could affect a developing fetus.

“For a lot of people, this was a wake-up call — and maybe the first wake-up call — that plastics were not universally good,” Ryan says.

So BPA became a lightning rod for debates about the safety of chemicals that can act like hormones in the body.

“As a physician, as a father, I would never on purpose expose my own children to BPA — I would not do it,” pediatrician Alan Greene told a 2009 rally in California in support of a bill to ban BPA in products for young children.

The plastics industry responded with messages reassuring the public that “the trace amounts we are exposed to from materials that keep our food safe are safe for us.”

Humans and hormones

Scientists remain divided on the safety of BPA, phthalates and many other chemicals that can act like sex hormones, and the intrauterine position phenomenon has contributed to that debate.

Early on, research suggested that a fetus’s position in the uterus could affect the very experiments used to assess the safety of BPA.

One study in the 1990s, for example, found that female mouse pups that had developed between two males were much less sensitive to BPA compared with female pups that had gestated between two other females.

This meant that scientists needed to account for a mouse’s place in the womb or they might miss any effects from BPA.

And if hormones from a sibling were enough to confound an experiment, so might lots of other subtle factors, like the mouse strain used in an experiment, the kind of test used to measure BPA or the possibility that trace amounts of BPA had contaminated an experiment.

Today, scientists are still trying to understand those factors.

They are also trying to figure out whether the hormonal changes related to intrauterine position can affect people.

“Some studies have shown that opposite-[sex] twins, especially the females, do show differences in behavior and may show differences in physiology as well, ” Ryan says.

These differences include how many children they have, how their facial features develop and how their brains process language.

But it’s difficult to know for sure, Ryan says, because it’s really hard to study a species that lives in the world, not a lab.