Mast Cell Tumor In Dogs: Diagnosis, Treatment & More

To keep the lights on, we receive affiliate commissions via some of our links. Our review process.

Lumps and bumps can be a normal part of life for any dog, especially when they hit their middle or golden years. Thankfully, many of these lumps are benign and cause no problem whatsoever. But unfortunately, just like people, dogs can get cancer in and under their skin.

The most common type of skin cancer in dogs is a mast cell tumor (MCT), alternatively, mast cell sarcoma or mastocytoma. They can often be successfully treated if caught early enough and dealt with aggressively, so owners need to be on the lookout. Let’s dive in to learn more about mast cells and what to do when they misbehave.

What Are Mast Cells?

Mast cells are part of the white blood cell family, the soldier cells of the immune system. These cells work together to protect the body against infection. Mast cells are a bit different from other white blood cells. They don’t circulate in the bloodstream but stay inside tissues that interface with the outside world, such as the skin and the intestinal and respiratory tracts.

Mast cells are equipped with little clusters of powerful biochemicals inside them, like little bombs, which are released when the mast cell is triggered. While this response is designed to be an efficient means of attack toward parasites, things can sometimes go wrong if the mast cells have become sensitive to something else, like pollen, bees, or peanuts. You have guessed it: one of the main components of mast cell granules is histamine, and misbehaving mast cells are responsible for allergic and even anaphylactic reactions.

What Are Mast Cell Tumors?

As though allergies weren’t enough trouble, mast cells can also start dividing uncontrollably and form a tumor. We are not sure why this happens exactly, but many of these tumors in dogs and cats have shown a genetic mutation inside the mast cell. These tumors also seem to affect certain breeds more than others.

A mast cell tumor can happen anywhere in the body where mast cells live, but most often starts from the skin (dermis) or just under the skin (subcutaneous). They are the most common form of skin cancer in dogs, accounting for around 20% of all skin cancers. While they may look very benign and well-isolated on the surface, mast cell tumors are remarkably pesky as they have the shape of a jellyfish, with long tentacles reaching out into the surrounding tissues. This makes them more challenging to remove than other lumps, especially in areas where there might not be a lot of skin to spare. This is why a mast cell tumor on a dog’s back leg, for example, can be challenging to manage if it is allowed to grow.

Are Certain Dogs More Likely To Develop Mast Cell Cancer?

Most dogs who develop a mast cell tumor are a bit older, though some reports are in younger dogs, especially Shar-Pei. The average age reported is eight to nine years old, and the chances seem evenly split between male and female dogs.

Any dog can have a mast cell tumor, but some breeds have an incredibly high rate, suggesting some genetic component. These include dogs with a flatter nose, such as Boxers, Bulldogs, Bullmastiffs, Boston Terriers, Pitbulls, Staffies, and Pugs. Other breeds with higher rates include Beagles, Rhodesian Ridgebacks, Weimaraners, Vizslas, Labradors, and Golden Retrievers.

What Do Mast Cell Tumors Look Like?

Frustratingly, both skin and subcutaneous mast cell tumors can mimic almost any other skin lesion in dogs (like a fatty lump, a wart, or a bump) and look or feel completely benign. This has earned them the nickname of “great imitators.” This means you cannot tell whether a lump is harmless or not by looking at it or feeling it. To know for sure, it needs to be aspirated with a needle.

Some mast cell tumors give us more of a clue about their nature because their size can change noticeably overnight or become suddenly swollen after being handled. This is because the tumor can be unstable and release histamine, causing the lump to become rapidly swollen, red, and itchy.

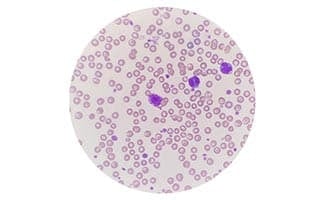

Diagnosis

If you have noticed a new lump on (or under) your dog’s skin, especially a fast-growing lump, it’s best to show it to your vet. They can often aspirate the lump quite easily with a small needle (this is called a fine needle aspirate) and have a look under the microscope.

If the result comes back positive for mast cells, then a few more steps are usually needed to better understand how to best tackle the problem, as not all mast cell cancers are equal. These steps are called grading and staging.

Grading

Mast cell tumors can be tricky and behave very differently based on their “grade,” essentially their suspected degree of malignancy. Pathologists and oncologists use different grading systems to find the best answer to the big questions: how is this tumor likely to behave, and how aggressively should we tackle it? One of the most common systems used is a 1-2-3 grading system, but other methods can also be used to complement it.

Without wanting to oversimplify the issue too much, it can still be helpful to think of mast cell tumors in terms of three grades:

Grade I

Though still quite locally pesky and invasive (remember the image of the jellyfish), a grade I tumor is usually fairly well behaved and is not trying to spread aggressively. These tumors behave benignly, which means that if the entire tumor is removed by surgery, then the problem is solved. This is the case for about half of all mast cell tumors.

Grade II

A grade II tumor has more unpredictable behavior, and this is where additional testing can help decide how to best approach the situation.

Grade III

A mast cell tumor given a grade III is sadly very invasive and aggressive. It can spread to the surrounding tissues and other lymph nodes, the spleen, and even the bone marrow. These aggressive forms represent about 25% of all diagnosed mast cell tumors and come with a much worse prognosis.

Staging

The next step of the diagnostic process is called staging. This means looking at whether the tumor appears to have spread past its initial location (metastasis) or is impacting the rest of the body. This helps get a complete picture of the situation and usually involves checking basic bloodwork, getting a sample of the relevant local lymph node, taking chest X-rays, and performing an abdominal ultrasound.

Treatment

Surgery

Thankfully, surgery is often curative for many grade I and even grade II mast cell tumors, as long as the tumor has been completely removed. This is called having “clean surgical margins.” Since the surgeon can’t tell whether they’ve managed to remove every last bit of tumor by just looking, generous margins are usually taken. As mentioned above, depending on the lump’s location on the body, this is not always possible. So it’s essential to understand that a “revisit” surgery can often be needed.

Non-Surgical

In some other cases, different treatment methods might be recommended, in addition to or instead of surgery, depending on each case. These methods usually require referral to a specialist center and might include:

- radiotherapy (either with or instead of surgery)

- chemotherapy for mast cell tumors that have spread

- a novel treatment called Tigilanol tiglate came out in 2020. The product is injected directly into the tumor and has shown a lot of promise in managing certain cases, especially where aggressive surgery would be challenging because of the tumor’s location (on a limb, for example).

Frequently Asked Questions

Below are some of the most frequently asked questions about mast cell tumors from pet parents.

Can A Mast Cell Tumor Be More Aggressive Based On Its Location?

Without being definitive, studies do suggest that tumors arising from a dog’s muzzle, nose, or scrotum seem to be more aggressive. If you notice a lump in these areas on your dog, best to have it looked at as soon as possible.

Can My Dog Get Another Mast Cell Tumor If One Was Just Removed?

It’s unfortunately common for certain dogs to have several mast cell tumor occurrences in their life, as there is a genetic predisposition. But don’t be disheartened: if another tumor comes up in a new spot, this is seen as a separate event, not a metastasis, and should be dealt with in the same way as if it were the first time. The prognosis for each new tumor starts fresh and is not usually affected by a dog having had another lump previously.

What Is The Difference Between A Mast Cell Tumor And A Histiocytoma?

Histiocytes belong to the same family as mast cells and can also form skin tumors. Histiocytomas are less common, tend to be smaller, often occur in younger dogs, and are benign but unfortunately cannot be told apart from their more pesky cousins without a fine needle aspirate.

Tagged With: Cancer