Talking About Your Myasthenia Gravis

They were just going to the movies. But the theater was way too hot. By the time they left, he couldn’t even hold his head up. He couldn’t speak. And he certainly couldn’t walk.

“Fortunately, I had my wheelchair,” says Zach McCallum. “But I was a mess.”

McCallum, 55, was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis (MG) in 2015. Since then, he’s spoken a lot about his condition. But he felt “really embarrassed” that day. It was early in his illness, and he didn’t want his sister to see him like that.

Then she gave him a message that stuck with him, and it’s one he brings to others in the MG community: It doesn’t help your friends and family if you hide this.

“It helps if you’re honest about what you’re living with,” McCallum says.

If you’ve been diagnosed with MG, here are a few tips on how to talk to your loved ones.

How to Get the Conversation Going

MG is a rare neuromuscular disorder. If your experience is anything like McCallum’s, most people you talk to probably haven’t heard of it. It’s also a disease you can’t see from the outside. That can make it tough for friends and family to grasp what you’re going through.

“It’s a different story if you’ve lost a limb,” says Amit Sachdev, MD, assistant professor and director of the Division of Neuromuscular Medicine at Michigan State University. “But in myasthenia gravis, the issue is fatigue and weakness.”

Families can sometimes have a hard time understanding why someone who looks fine can’t get up and do the dishes or needs help to the bathroom, Sachdev says. But they might see things a little clearer if you explain some medical stuff.

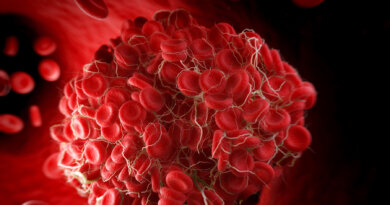

Tell your friends and family that you have an autoimmune condition. Your immune system attacks certain muscle receptors faster than your body can make new ones. This extra inflammation “blocks the nerves from talking to the muscles,” Sachdev says.

With MG, that commonly affects how you move your eyes, mouth, arms, legs, or breathing muscles.

A not-so-scientific analogy may also help get your point across. McCallum likens MG to a broadcast station and a TV or radio set.

Your nerves send out a signal to “lift your arm or lift your leg,” McCallum says. “But little jerks have been running around in the bloodstream destroying people’s receivers. So now the muscles aren’t getting the signal … and the more you use your muscles, the more receivers get blocked.”

If they want more info about the ins and outs of your condition, send them to the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America’s website.

Go Over Your Day-to-Day Life With MG

Richard Nowak, MD, director of the Yale Myasthenia Gravis Clinic, says your first talk with loved ones will differ depending on where you are in your disease course. Your symptoms may change or become easier to control as you decide on the best treatment plan, he says.

But whether you’ve just been diagnosed or have lived with MG for a while, let your friends and family know which symptoms have a big impact on your day-to-day life.

For instance, double vision or droopy eyelids can make it hard to drive or read. As you learn to manage your MG, Nowak says, you may need help getting to your doctor’s appointments, picking up your prescriptions, or going to the grocery store. And tell those close to you that it’s common for some of your symptoms to come and go.

You may feel perfectly fine in the morning, Nowak says, but by midday, afternoon, or early evening, you may have trouble keeping your eyelids open or talking. That change might confuse your friends and family if they don’t know what to expect.

“Sometimes with slurred speech, people say, ‘Have you gotten enough rest, or have you been drinking?’” Nowak says. “It can be very easily misinterpreted as something else going on when that’s not the case.”

Some MG symptoms can be serious. Tell your loved ones to keep note of any shortness of breath or swallowing issues. They should get medical help right away if you’re having trouble breathing.

Bring Up Long-Term Symptoms

Medication and other therapies can be a big help for the majority of folks with MG.

“We can get most patients symptom-free or with minimal symptoms that don’t necessarily affect their day-to-day activities,” Nowak says.

But treatment isn’t a magic bullet for everyone. McCallum has a refractory form of the disease. Fast-acting medication helps some of his symptoms. But he still has a lot of weakness, especially in his legs. He uses a wheelchair or other aids for long distances.

“I can walk around in the house,” McCallum says. “When I use my forearm crutches, I can walk 40 feet before I have to stop, or I’ll fall down. That’s my limit.”

On top of tired muscles, McCallum gets a lot of general fatigue and brain fog. He says those close to him know how to spot the signs he needs to rest.

“When I’m with my friends in the grocery store, and we’re looking at a bunch of grapes, and I’m like, ‘Oh yeah, let’s get some ‘beads,’” McCallum says. “It’s not because I don’t know the word for grapes, and I’m suddenly having aphasia. It’s that my brain was just, like, ‘I’m too tired to find the right word so I’m just going to pick one.’”

Explain What Life With MG Feels Like

No one can ever know exactly how you feel. But there might be some tests that’ll give people a small idea of what some of your symptoms are like.

“There are computer screens that will simulate what double vision looks like,” McCallum says. “Or you can say, ‘Strap on a 10-lb weight to each wrist and now do all the things you need to do.’”

Sachdev says it’s tricky to try to find the right example. But you can tell someone without MG to bring to mind how weak and tired they feel after exercising really hard or going for a long run.

“Think about how much effort it took to get to that point,” Sachdev says. “Now think about your daily activities taking you to that point.”

How to Show Support for Someone With MG

McCallum lives alone, but he worked with an ADA-compliant designer to remodel his living space. His kitchen and bathroom are now wheelchair accessible, and he put in a stairlift. These kinds of adaptive changes are something to think about if you live with someone who has MG.

As a friend or family member, you can also pitch in with everyday things. McCallum’s pals may do a load of laundry or clean up his dishes. And they show they care in subtle ways.

“A lot of times they’re just doing little thoughtful things: ‘I saw this reaching tool and I thought you would find it useful,’ or ‘I read this interesting article about the way the immune system works, and I wondered what you thought about it.”

If you have MG, McCallum says to tell your friends and family when they’re being unhelpful. Give them a chance to change for the better. But “if you come away from a conversation with somebody thinking, ‘Well, maybe I do really just need to try a little harder. Maybe I am just being a little bit lazy,’ then that’s not a good friend. That’s not somebody you want to be with.”