The Unlikely but Promising Partnership of Comics and Health Care

A while back, indie comics artist Sam Hester found herself spending endless hours in the hospital, not as a patient but as primary caregiver for her mother, Jocelyn, a longtime Parkinson’s patient who had recently begun to hallucinate – she saw ghost-like figures surrounding her – while exhibiting signs of early-stage dementia.

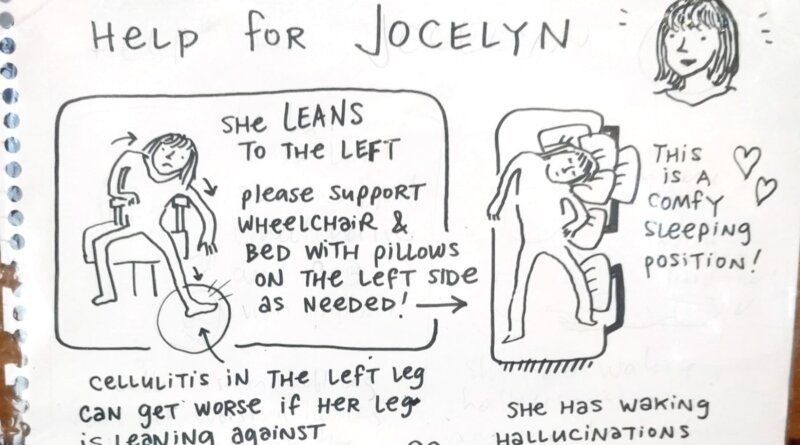

Then another symptom kicked in. During a hospital visit, Hester observed her mom leaning off to the left, her body slumped sideways. Hester was torn: She wanted to alert the night nurses but urgently needed to get home to her children. That’s when she came up with the idea of conveying her message through simple drawings, which she titled “Help for Jocelyn” and taped over her mom’s bed. One sketch illustrated Jocelyn’s new symptom, with a problem area circled; another showed her in bed, artfully supported by pillows. Next to that one, Hester wrote, “This is a comfy sleeping position!”

The next morning, she found Jocelyn sleeping comfortably, just as the drawing depicted her. From then on, Hester brought pictures to every doctor appointment, using them as a kind of visual shorthand. And that eventually led her to the emerging but still not widely understood field of “graphic medicine.” The term was coined in 2007 by Dr. Ian Williams, a graphic novelist and doctor based in Hove, England, who defines it as “the intersection between the medium of comics and the discourse of health care.”

For Hester, this was a sweet spot. Although she has no medical training, she had begun creating autobiographical comics in art school back in 1997 and found them a good way to tell stories about health challenges and other personal struggles. She later became a leader in graphic recording – another emerging field – which entails listening to lectures or conversations, picking out key ideas, and presenting them in a visual form. When Hester learned about graphic medicine in 2016, it struck a familiar chord. As she puts it, “I realized that, in some ways, I’d been a practitioner of graphic medicine all along.”

Graphic medicine takes many forms, reflecting both patient and medical practitioner points of view. It includes visual narratives that run the gamut from patient memoirs to biographies of medical researchers to dystopian pandemic stories. In fact, any comics that deal with issues surrounding physical or mental health can be considered graphic medicine – and professional drawing ability isn’t a requirement. A transgender person seeking gender-affirmative surgery, for example, might create comic panels to explain how a procedure could improve their quality of life. Or a child can draw stick figures to show exactly what hurts.

Uses for Comics Range From Teaching to Therapy

Research suggests countless other applications. A 2018 study conducted at a medical college in New Delhi found that while less than 22% of its students had even heard of graphic medicine, nearly 77% favored the use of comics as a teaching tool in India. Last year, a project based on fieldwork in Norway brought together a social anthropologist, a graphic artist, and people with drug addictions to combat the stigma associated with illegal drugs and hepatitis C. Another 2021 study, published by Springer, saw therapeutic potential in comics created by cancer patients, citing the medium as a way to “explore their medical traumas” and a path to “reanimating their bodies.”

“Do comics work … in educational settings? Can reading comics help physicians better understand the patient experience? Can we really help build empathy through reading comics? These, and many more, are all questions explored in graphic medicine,” says Matthew Noe, a lead librarian at Harvard Medical School who serves on the boards of both the Graphic Medicine International Collective and the American Library Association’s Graphic Novels and Comics Round Table.

Community building is another aim of graphic medicine. Insisting that anybody can draw, its practitioners invite everyone involved in health care – doctors, nurses, and public health workers as well as patients – to share their own stories. For patients, this provides a sense of agency. Creating comics can also help medical professionals grapple with their own trauma. “We take the collaborative nature of comics and the understanding that health is a community project and come together to share, learn, and support people,” Noe says. “This has been the most important thing, especially during the pandemic.”

Comics naturally lend themselves to humor, irreverence, and a freedom of spirit, which gives patients a fresh means of communicating with doctors. “Autobiographic graphic novels derive from a sort of underground, subversive aspect of comics, where people talked about edgy or taboo subjects such as sex or drugs,” says Williams, who is also co-creator of the Graphic Medicine website. “[These] novels retain a sense of ironic humor, which can be very joyful, but also get into a lot of details about lived experiences of patients that medical textbooks may not cover.” Comics, he adds, can reveal “problems that may never cross your mind as being associated with a specific condition,” potentially important information when it comes to making a diagnosis.

Giving the Patient a Voice

At the same time, graphic medicine offers patients something that’s often missing in a formal medical setting: the feeling that their voice is being heard. Even those who have dementia can use it to document their journey and keep a record of their symptoms – or to express themselves through collaboration with a caregiver. This was confirmed by a 2021 research project involving multiple universities in the U.K., part of a larger study titled “What Works in Dementia Education and Training?” It found “graphic storyboarding” more likely than academic text to foster empathy.

Having your voice heard is, of course, especially difficult when there’s a language barrier. In the U.S., where health care information is usually communicated in English, only 6% of doctors describe themselves as Spanish-speaking, even though 18.9% of the population is Hispanic and that number is on track to reach 25% by 2045. For those who aren’t fluent in English, pictures clearly help. The demographic trend also signals a growing need for creative solutions like the bilingual Comic of the Day, by Elvira Carrizal-Dukes, PhD, a series of health-related comics that address the diverse community of El Paso, TX.

Too often the voice of the patient is subsumed by the voice of the doctor. When patients are bombarded by new information, often expressed in medical jargon, it becomes difficult to absorb. Questions that might occur to them fall by the wayside. And the problem may be compounded by sexism, as evidenced by studies showing that women wait longer than men for emergency care and are less likely to be given effective pain medication. Writer-illustrator Aubrey Hirsch recounts her own experience of this bias in “Medicine’s Women Problem,” a graphic memoir that recalls doctors diagnosing her “based on my age and gender, and not my actual symptoms” (one of their preconceptions boiled down to “young+female=eating disorder”), with the result that her autoimmune disease went undetected.

In pediatrics, meanwhile, the value of graphic medicine seems self-evident, given the difficulty children may have explaining both symptoms and their emotional reaction to being sick. A child who isn’t familiar with the term “burning sensation,” for example, might express that feeling by drawing fire on a human body. And when it comes to drawing, kids tend to be less inhibited than adults.

Graphic medicine can also be useful in explaining to children everything from potty training to minor surgery, according to Jack Maypole, MD, director of the Comprehensive Care Program at Boston Medical Center and associate clinical professor of pediatrics at Boston University School of Medicine. “It helps them better understand the procedures they are going through,” says Maypole, adding that comics “can even be used in therapeutic settings – say, in art therapy, to help children process their emotions.”

Graphic Medicine’s Global Future

Cartoonist M.K. Czerwiec, RN – aka “Comic Nurse” – considers all of this just a beginning. A co-author, with Williams and others, of Graphic Medicine Manifesto, she teaches a course in comics at Northwestern Medical School and envisions a more global role for them in the future. “I would like to see cross-cultural exchange across graphic medicine movements internationally,” Czerwiec says. Such an exchange, while generally promoting cultural awareness, would help doctors treat immigrants, who may have different presentations of a disease. Symptoms of depression, for example, are known to vary based on cultural beliefs.

Proponents of graphic medicine say it needs to be taught more widely in medical schools – and to reach everyone involved in the health care system, including orderlies, maintenance staff, and even receptionists. That might benefit trans people, for example, who have reported feeling uncomfortable in waiting rooms of clinics, where they may feel judged or discriminated against. Educating intake receptionists with comics that explain the trans experience through accessible images and jargon-free language could alleviate the problem. One advantage of the medium is its simplicity.

Another is the way it can evoke emotion. Last year, Sam Hester spread the gospel of what she calls the “unlikely partnership between health care and comics” in a TEDx Talk which has chalked up nearly 2 million views on YouTube. “Just imagine if your new doctor opened your chart and saw pictures that sparked curiosity about the person, not just the symptoms,” she said toward the end of her talk. She then added:

“When I looked at all the pictures I’ve drawn of my mom, I did see her symptoms. But I also see my mom. She’s there, in all the words and pictures that have continued to hold us together.”