Why We Can’t Test Our Way Out of This

What your doctor is reading on Medscape.com:

MAY 06, 2020 — At the moment, society is locked down in an attempt to reduce the spread of the coronavirus. The streets are quiet, the economy has come to a halt, and 30 million people are unemployed. The conventional wisdom in the United States is that more testing will be our pathway out of this quagmire, despite the fact that we are running large numbers of tests daily. As of May 1, about 6 million tests have been performed in the United States. In the nation’s epicenter, New York, close to 1 million tests have been performed.

Relatively speaking, the state of New York is currently testing at five times the rate of the frequently cited gold standard, South Korea. But this is not enough, we are told. Public health experts have called for more testing, and at least one Nobel Prize–winning economist has even called for everyone in the United States to be tested. A closer look at the performance of the tests we have, however, raises serious doubts that expanding testing will be a cure-all.

Why Testing Everyone Is a Bad Idea

There are basically two types of tests available for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19: RT-PCR and serologic testing.

RT-PCR is used to directly detect presence of the virus itself, but it has limited sensitivity (about 40%-60%) and cannot be used to exclude the presence of the virus. Serologic testing for antibodies is more sensitive later in the course of the disease, but it can also yield a false-negative result because it may take weeks to develop antibodies in the blood, or they may be present in amounts that fall below the threshold for detection.

The advantage of RT-PCR tests is that they are highly specific and can effectively rule in the presence of the virus. Serology tests are vulnerable to cross-reactivity with other coronaviruses, raising the possibility of false positives. We also don’t know whether the presence of antibodies establishes immunity or how long the antibodies for this novel virus will last.

Continued

What’s important to patients and clinicians is the positive or negative predictive value of a test, a value highly dependent on the level of suspicion that led us to order the test in the first place. We don’t recommend randomly testing people walking down the street for colon cancer because we don’t want our test sample to have lots of twenty-somethings with no risk factors for colon cancer. The lower the pretest probability of finding disease, the lower the chances that a positive test is accurate. The same logic applies to testing patients who have a very high likelihood of disease. Someone who presents with a fever, cough, and characteristic oropharyngeal plaques of Streptococcus doesn’t need a test; they need an antibiotic. A negative result in this case is most likely wrong.

For exactly these reasons, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for testing prioritize patients with a higher risk of having COVID-19.

Even broadening the indications for testing, as the CDC did recently by adding headache to the list of possible symptoms, runs the risk of making these tests less useful. Testing everyone in the United States every single day, even if possible, would be a bad idea.

Testing to Track Prevalence of Disease

What would be helpful is understanding the prevalence of circulating SARS-CoV-2 in the community. This would allow more targeted testing and may help policymakers and the wider public better understand the lethality of the virus. This is best done through serologic (antibody) testing, but this has its own challenges.

Because we’re dealing with a novel virus, many of the tests are being used under Emergency Use Authorization and have not been validated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Validating tests is not without its own uncertainties. Estimating the specificity of a test requires validation against known negative samples. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, we can’t just use people with no symptoms as negative controls because it is believed that many infected people can be asymptomatic. Another approach would be to take people with a recent confirmed infection with another coronavirus. This would be attractive because it would directly examine the test’s ability to cross-react with other coronaviruses, but it also runs the risk of including patients with SARS-CoV-2 coinfections. The best approach is probably to use samples stored prior to the onset of the current outbreak, ideally around the time of year when other coronaviruses circulate, to test for cross-reactivity, although even this is imperfect. We don’t know exactly when other coronaviruses circulate, and the antibody response may wane over different periods of time. With these limitations in mind, what do the current best data tell us about serologic prevalence in the United States?

Continued

One study by a group of Stanford researchers (in pre-print and not yet peer reviewed) attempted to estimate the seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California. Santa Clara had the largest number of confirmed cases in any county in Northern California and the earliest known case of COVID-19 in the United States.

The Stanford team used a SARS-CoV-2 lateral flow immune assay from Premier Biotech in Minneapolis, Minnesota. They first validated the test using confirmed COVID-19 sera and pre-COVID era controls, and calculated a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 99.5%.

They used targeted Facebook ads to recruit participants. More than 3000 adults agreed to have their blood drawn, and 50 tested positive for IgG or IgM antibodies, which translated to a crude prevalence rate of 1.5%. Weighting the sample to match the county by zip code, race, and sex increased the prevalence rate to 2.8%. Based on this, the Stanford team initially estimated that between 48,000 and 81,000 people had been infected in Santa Clara, which was 50-80 times the number of confirmed cases at the time. Their results suggested an infection fatality rate of 0.1%-0.2%.

The Stanford figures were criticized by those who suggested that there was too much uncertainty to make these estimates from the small sample that was studied. Very small changes in the specificity of the non-FDA-validated test conceivably make it possible that all of the positive tests in the study were false. Even so, most everyone believes that the official tally of confirmed cases of COVID-19 is a significant underestimate. A skeptical critic who did a Bayesian reanalysis of the Stanford data still arrived at a prevalence that was 20 times higher than the reported cases and an infection fatality rate of 0.5%.

Meanwhile, on the East Coast, the first release of seroprevalence data from New York, the center of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States, came via Governor Andrew Cuomo on April 23. Results from 3000 antibody tests for IgG taken from a sample of people out shopping for groceries suggested a 20% prevalence of disease in New York City, which roughly translates to 1.7 million infected New Yorkers. This suggests an infection fatality rate of 0.9%, a much higher estimate than in the California studies, though still much lower than many have feared.

Continued

Many, like leading virologist Florian Krammer, thought that 20% was too high a number and asked for more details on the test. But Venk Murthy, MD, a cardiologist and expert on diagnostic testing, walked through a theoretical exercise assuming a worst-case scenario where all tests done outside of the New York metropolitan area were false positives, and concluded that a 20% prevalence in New York City is indeed plausible.

The implications of these numbers from a testing standpoint suggests that even though the circulation of the virus far exceeds the number of confirmed cases, the vast majority of the country probably has a prevalence rate in the single digits. This means that our efforts to significantly broaden our currently available tests, especially if we include asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic low-risk individuals, could hurt more than help.

Will Adding Contact Tracing Boost the Utility of Testing?

The push for more testing is coupled with the push for contact tracing, particularly of the digital kind. However, relying on smart phone app-based contact tracing to identify those who should self-isolate has many practical difficulties.

For it to work, it would require about 60% of the population to install a contact tracing app, according to estimates from the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Medicine. Even in non-libertarian, rule-following Singapore, the number that installed the TraceTogether app is closer to 20%. It’s also notable that Singapore, a very small country with a population of 5 million, had a significant outbreak that forced a widespread lockdown despite its widely praised and ballyhooed app-based contact tracing.

With app- or non-app-based Bluetooth tracing such as the Apple and Google collaboration, a familiar problem rears its head again: false positives. Bluetooth goes through walls, so city apartment dwellers could register a contact with a downstairs neighbor they’ve never met or with someone who jogged by. Technology from Silicon Valley has a cool factor that seems to mesmerize large swaths of the public and government officials into sending them lots of taxpayer dollars for solutions that don’t work well—think electronic health records. Layer this on top of tests that are far from perfect, and you have a very high mountain to climb to make this approach work.

Continued

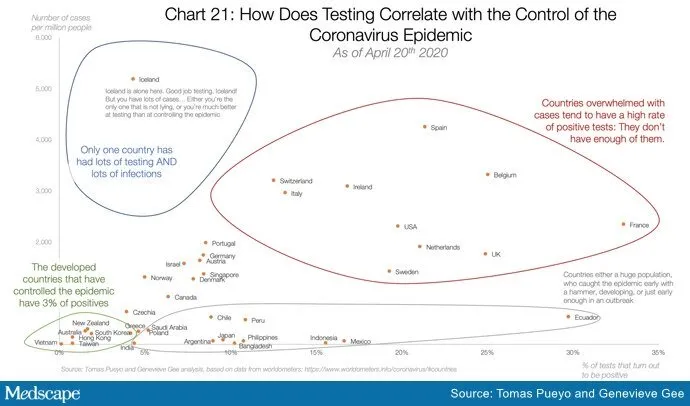

The enthusiasm for testing seems to derive from the general idea that countries that test a lot have the lowest death rates. One such chart making the rounds is shown below.

The circles may seem compelling, but beyond the foolishness of confusing correlation and causation, even correlation is hard to find when you try to draw a line through these data points. The graph below (with country names omitted for ease of viewing) was adapted from one provided by Andrew Foy, MD (cardiologist, Hershey, Pennsylvania) and confirms what’s obvious to the naked eye: There is little correlation between amount of testing and control of the epidemic.

This should not be surprising given that the more-testing-equals better-control hypothesis papers over the vast differences in countries in regard to size, density, geographic location, demographics, connectedness, and policies related to travel and social distancing. It also fails to appreciate differences in testing availability and assumes that COVID-related death counts are accurate everywhere.

None of this is to say that testing is not important. It is absolutely vital to be able to test the right people in order to track the spread of an outbreak in communities. Testing will surely inform the public and policy makers in regard to personal behavior as well as mass-mitigation steps that may need to be taken. But testing is no panacea. The most intelligent path forward incorporates appropriate testing, not indiscriminate testing, to keep the virus at bay when the country inevitably opens.

Anish Koka, MD, is a cardiologist in private practice in Philadelphia. He comments frequently on healthcare absurdities and on healthcare policy. He is also a cohost of the Accad & Koka Report Podcast.