P-22, late LA mountain lion, makes a wildlife crossing possible : NPR

[ad_1]

A volunteer carries a cardboard cutout of mountain lion P-22 during the groundbreaking ceremony for the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing in Agoura Hills, Calif., in April.

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

A volunteer carries a cardboard cutout of mountain lion P-22 during the groundbreaking ceremony for the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing in Agoura Hills, Calif., in April.

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

Los Angeles is mourning its beloved mountain lion P-22, who was euthanized over the weekend due to health issues including injuries sustained from a vehicle strike.

It’s a tragic ending for an animal who made his name by traversing two major freeways — a dangerous and unprecedented feat — to take up a lonely residence in Griffith Park. Over his 12 years, P-22 came to symbolize the challenges facing urban wildlife as well as one particularly groundbreaking effort to protect it.

That’s the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, a vegetated overpass that will eventually link the Santa Monica Mountains to the Simi Hills, reconnecting an ecosystem that has long been fragmented by a major freeway.

The 210-foot crossing will span 10 lanes of the U.S.-101 Hollywood/Ventura Freeway, and is set to be the first of its kind in California and the largest in the world when it is completed in 2025. Construction on the project, supported through a public-private partnership, started in April after decades of research and years of fundraising.

In statements mourning P-22’s death, wildlife advocates, government agencies and California Gov. Gavin Newsom credited the cougar with inspiring conservation efforts and said the Hollywood icon’s legacy will live on.

“The Annenberg Wildlife Crossing did not come soon enough for P-22, but it will protect future mountain lions and other animals and ensure a safer future for them and our planet,” the Annenberg Foundation said in a statement.

Beth Pratt, the California regional executive director for the National Wildlife Federation, told Morning Edition that P-22’s story both showed why such a crossing is necessary and helped to make it a reality.

“He wasn’t just a celebrity influencer. He was someone who used his celebrity for good … and put a real story to the impact of these highways,” she said. “And here we are with the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing. We got donations from all over the world and it’s because of him.”

The lion’s LA lifestyle made him — and his cause — famous

P-22 made his way to Hollywood from the Santa Monica Mountains by crossing two of the busiest freeways in the world, then proceeded to live in Griffith Park — “the smallest home range that has ever been recorded for an adult male mountain lion,” per the National Park Service — for more than a decade.

“It’s a remarkable story … nobody would predict that a mountain lion would march 50 miles across two of the busiest freeways, through Beverly Hills, close to Hollywood Boulevard to make a home under the Hollywood sign,” Pratt says.

He became a local legend, sometimes appearing in neighborhoods (once underneath an LA home) and captivating residents with his hijinks (including a dramatic recovery from rat poison).

The so-called “Brad Pitt of mountain lions” gained further notoriety after National Geographic published a photograph of him beneath the Hollywood Sign (right on his home turf) in 2013.

Photographer Steve Winter, who captured the now-iconic shot, told NPR’s All Things Considered this week that he was blown away by the reaction to the image, and is confident P-22’s legacy will live on.

“I think we owe it to P-22 and all California wildlife to build more crossings and to connect more habitat. That’s what is needed,” he said. “I mean, now they’re teaching wildlife and P-22 in the greater LA school district. And every Oct. 22 is P-22 Day in LA. His legacy will live for years, if not decades, to come. No one’s going to forget P-22.”

P-22’s solitary survival story inspired many in LA and beyond. But, as the National Park Service said, he was “more than just a celebrity cat.”

“He was also a critical part of a long-term research study and a valuable ambassador for the cause of connectivity and for wildlife in the Santa Monica Mountains and beyond,” it said, adding that scientists will continue to analyze his data for years to come.

Pratt — who has a P-22 tattoo and a wardrobe of items with his face on them — told Morning Edition that the mountain lion also helped connect people to each other, and to “the wild world that needs saving.”

“That cat, through inspiring us, showed us what was possible,” she said. “He made us more human. He made us realize, even in the second-largest city in the country, that we needed a connection to wildlife.”

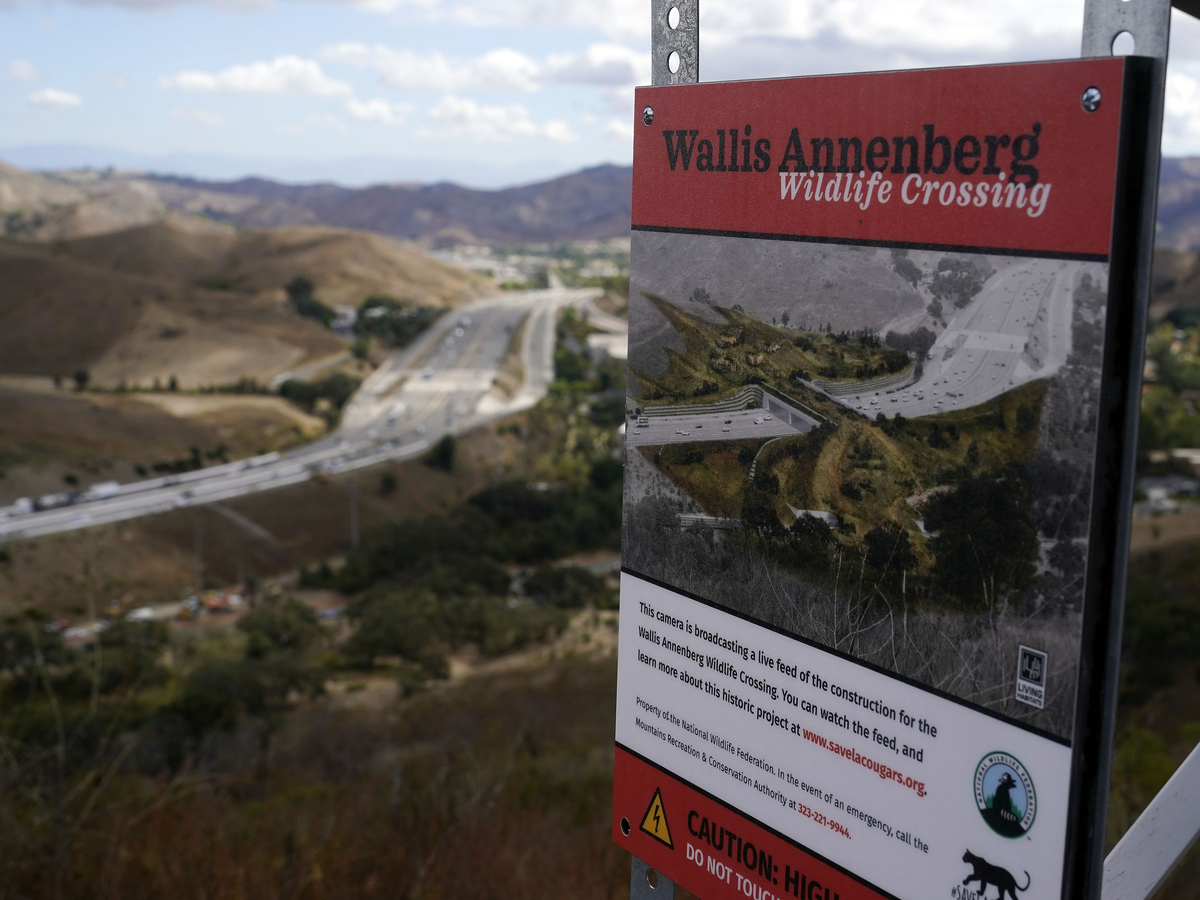

An overview of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, which will eventually be built over the 101 Freeway in Agoura Hills, Calif.

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

An overview of the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, which will eventually be built over the 101 Freeway in Agoura Hills, Calif.

Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP

The wildlife crossing addresses a longstanding problem

Decades of research underscore the need for a wildlife crossing to protect the flora and fauna of the Santa Monica Mountains, which have been isolated by development and highly trafficked roads.

At least 29 mountain lions have been killed by vehicles in the park service’s study area — which includes the Santa Monica range, Simi Hills, Santa Susana Mountains, Verdugo Mountains and Griffith Park — since 2002, and at least four have died on roadways this year alone.

A 1990 study commissioned by the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy identified this particular site — the Liberty Canyon Wildlife Crossing — as the necessary place to connect the mountains in order to prevent the local mountain lion population from extinction. Over the next three decades, the conservancy and other partners acquired much of that land (which had been largely privately owned) to make it possible to link the two areas.

“The purpose of the project is to provide a safe and sustainable passage for wildlife across US-101 near Liberty Canyon Road in the City of Agoura Hills that reduces wildlife death and allows for the movement of animals and the exchange of genetic material,” the conservancy explains. “Without a safe and sustainable wildlife crossing, movement between these remaining areas of natural habitat is severely restricted and wildlife within the Santa Monica Mountains is essentially trapped.”

Pratt explains that as it stands, the isolation of the Santa Monica Mountains creates a sort of “extinction vortex” where mountain lions are trapped (P-22 was one of the few to make it out alive) and forced to breed with their own family members, diminishing their genetic diversity and risking future generations’ ability to reproduce.

Advocates hope the crossing will help protect and promote ecological connectivity not just for mountain lions, but other forms of wildlife from bobcats to birds to lizards. It will offer safe passage for these animals to meet — and reproduce with — more members of their species. Pratt says it’s especially important for the mountain range to be resilient in the face of threats like climate change and wildfires.

The question is: What will make such a crossing appealing to animals who may be wary of the roaring traffic?

Pratt says it’s going to be covered with vegetation, to help minimize the sound and light from outside and essentially trick the creatures into thinking they’re not walking over a freeway. Picture a “beautiful ecosystem” with “trees and butterflies flying over it,” she says.

“And what I love to imagine is here we are in one of the busiest commuter roads and you’re going to have people commuting, you know, (300,000) to 400,000 cars a day,” she adds. “And once this is finished, while they’re doing that, they’re going to be driving under the structure [and] a mountain lion will be crossing over. That, to me, is pretty hopeful.”

The audio for this story was produced by Milton Guevara and Iman Maani, and edited by Amra Pasic.

[ad_2]

Source link